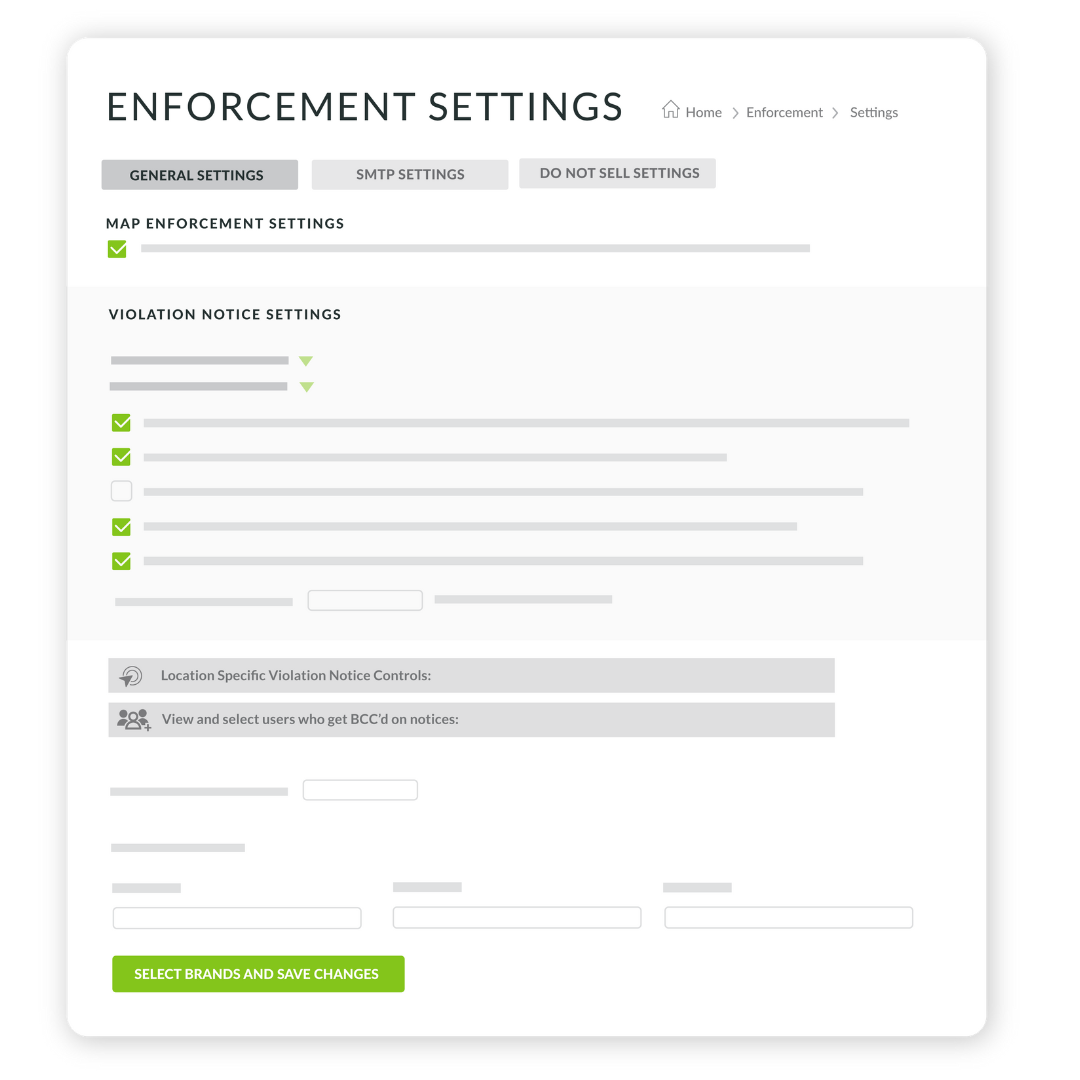

Customize your communication approach by selecting automated or manual violator communications, or a combination of both, with complete control over outreach tiers and levels. Opt for a fully automated experience for efficient communication or review communications before sending to maintain control over each interaction. Our solution empowers you, seamlessly adjusting to your unique needs, to ensure effective and efficient enforcement.

Customizable violation templates give you the power to tailor your enforcement messaging according to your needs. You can choose from the templates provided within our platform or create custom templates with desired content and messaging. Enjoy unlimited flexibility to create templates that reflect your unique requirements and tie them to specific enforcement actions or stages, allowing you to align with your brand’s identity and enforcement goals.

On Demand Notifications

As part of our commitment to providing you with cutting-edge solutions for your enforcement needs, this feature is designed to empower you with unprecedented control and transform the way you manage notifications within our system.

On Demand Notifications synergizes two existing TrackStreet features, Contact Merchants and Enforcement Templates, and takes it to the next level by adding additional functionality and flexibility. With this feature, you are no longer bound by predetermined workflows. Instead, whether you’re enforcing pricing policies, notifying unauthorized sellers, or even sending notices on data you receive from other sources not offering notification solutions, TrackStreet has you covered.

Key Features:

- Customizable Messages: Craft your own custom message or choose from templates you’ve created within Enforcement.

- Personalized Subject and Content: Tailor the subject and content of the email even after selecting a template.

- Recipient Selection: Just like email, choose to whom you wish to send the notice, and also add CC or BCC recipients.

- Preview and Send: Preview your message before sending it.

The Impact of Visibility

GAIN CLEAR INSIGHTS

How much of your ecommerce channel is hidden from view? Our market visibility offerings create a foundation for you to understand your online ecosystem™, prioritize revenue opportunities with the best partners, and take precise steps to control and optimize your channels.

The Tools to Expand

PROPEL YOUR GROWTH

Whether you are looking to better understand how inventory and revenue flow through your Amazon and marketplace presence, learn competitive insights, track international markets, or better manage strategic relationships for growth – we’ve got you covered.

Unlock

Your Brand’s Potential

Are you prepared to take your brand to new heights? Share your information with us, and let's begin the journey together.

In the Spotlight

Blogs, Insights & Thought-Provoking Bytes

Pricing Erosion: Definition, Causes, and How to Avoid It

Learn about pricing erosion, its root causes, and effective strategies for prevention.

How to Stop Unauthorized Sellers on Amazon

In the dynamic landscape of online marketplaces, challenges to maintaining equitable competition and brand integrity are ever-present. Unauthorized selling on platforms such as Amazon has emerged as a significant concern, rewarding unscrupulous diverters and resellers...

What is a MAP Policy and Why It’s Important for Brands (+ FAQs)

Introduction In the world of retail, stores that get the highest sales with the highest profit margins are the ones regarded as successful. To reach that achievement, an organization’s sales and marketing department must employ a variety of strategies to attract as...